Solved cyptopals, [set 2 challenge 12] Relevent code github

Lots of people know that when you encrypt something in ECB mode, you can see penguins through it. Not so many of them can decrypt the contents of those ciphertexts, and now you can

Little primer:

A block cipher is simply another name for a (strong) pseudorandom permutation. That is, a block cipher $F: \{0, 1\}^n × \{0, 1\} → \{0, 1\}$ is a keyed function such that, for all $k$, the function $F_k$ defined by $F_k(x) = F (k, x)$ is a bijection (i.e., a permutation). Where, $n$ is the key length of $F$ , and $l$ is its block length.

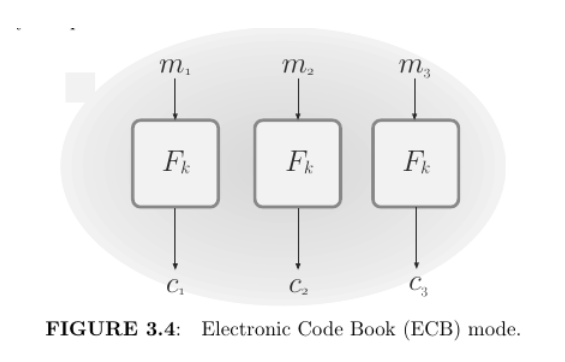

Electronic Code Book (ECB) mode. This is a naive mode of operation in which the ciphertext is obtained by direct application of the block cipher to each plaintext block. That is, $c := F_k (m_1), Fk (m_2 ), . . . , Fk (m’ )$ . Decryption is done in the obvious way, using the fact that $F_k$ is efficiently computable.

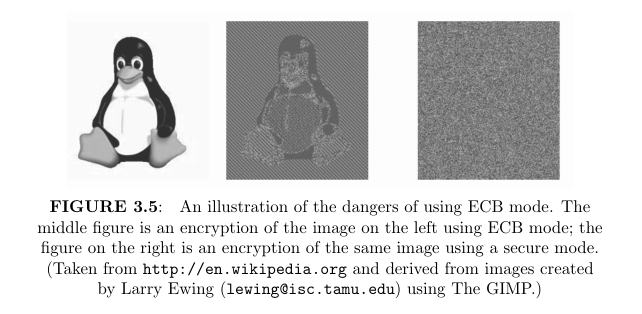

ECB mode is deterministic and therefore cannot be CPA-secure. Worse, ECB-mode encryption is not even EAV-secure. This is because if a block is repeated in the plaintext, it will result in a repeating block in the ciphertext. Thus, for example, it is easy to distinguish the encryption of a plaintext that consists of two identical blocks from the encryption of a plaintext that con- sists of two different blocks. This is not just a theoretical problem. Consider encrypting an image in which small groups of pixels correspond to a plaintext block. Encrypting using ECB mode may reveal a significant amount of infor- mation about patterns in the image, something that should not happen when using a secure encryption scheme. (Figure 3.5 demonstrates this.) For these reasons, ECB mode should never be used.

How to actually solve this?

We use a function AES-128-ECB(your-string || unknown-string, random-key) as a modified encryption oracle. By strategically devising “you-string” and quering this encryption oracle we can mount a form of chosen plaintext attack to decrypt this unknown-string

(we assume block size is 4 bytes, to demostrate this)

- To demonstrate assume the unkown string is $u_1, u_2, u_3, u_4, u_5, u_6, u_7, u_8$ “. To be encrypted in aes-cbc mode it’ll broken down into 2 blocks, where each block is of 4 bytes

Block1 : $u_1, u_2, u_3, u_4$

Block2: $u_5, u_6, u_7, u_8$

Now, let’s use the oracle and craft an input block that is exactly 1 byte short. So your-string=AAA. Our new payload that will be encrypted will be:

Block1: $A, A, A, u_1$

Block2: $u_2, u_3,u_4,u_5$

Block3:$u_6, u_7, u_8, x01$ (padding, ya know)

Enc(Block1= $A, A, A, u_1$) = $x_1, x_2, x_3, x_4$

Now to find $u_1$, you just iterate over all possible vaues and give then to the encryption oracle and stop when you reach $x_1, x_2, x_3, x_4$

for i in range(0,256):

ct = enc(AAAi)

if ct=x_1 x_2 x_3 x_4

print: u_1 = i

repeat the same for the entire block, then repeat the same for the next block, just compare the second block values.

A bit on possible values of i:

possible_chars = [10] + [i for i in range(32, 91)] + [i for i in range(97, 123)]

We do not use all possible values between 1 to 256. Here we assume that we have the priot knowledge that the plaintext is in english and contains only primatable ascii characters.

Binary value of 10 is LF(Line Feed) in ASCII, used for new line here

Binary values 32 to 90 are printable characters in ASCII

Binary values 97 to 123 are capital letters

Technically, it’s all pritned in UTF-8, the good thing is that all unicode maps the same binary values as ascii does.